Complete article

Spring 2006, Vol. 38, No. 1

By Thomas Putnam

Researchers come to the Hemingway archives at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library primarily to examine Ernest Hemingway's original manuscripts and his correspondence with family, friends, and fellow writers. But upon entering, it is hard not to notice the artifacts that ornament the Hemingway Room—including a mounted antelope head from a 1933 safari, an authentic lion-skin rug, and original artwork that Hemingway owned.

Though not as conspicuous, one object on display is far more consequential: a piece of shrapnel from the battlefield where Hemingway was wounded during World War I. Had the enemy mortar attack been more successful that fateful night, the world may never have known one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. Conversely, had Hemingway not been injured in that attack, he not may have fallen in love with his Red Cross nurse, a romance that served as the genesis of A Farewell to Arms, one of the century's most read war novels.

Hemingway kept the piece of shrapnel, along with a small handful of other "charms" including a ring set with a bullet fragment, in a small leather change purse. Similarly he held his war experience close to his heart and demonstrated throughout his life a keen interest in war and its effects on those who live through it.

No American writer is more associated with writing about war in the early 20th century than Ernest Hemingway. He experienced it firsthand, wrote dispatches from innumerable frontlines, and used war as a backdrop for many of his most memorable works.

Scholars, including Seán Hemingway, the author's grandson and editor of the recent anthology, Hemingway on War, continue to use documents and photographs in the Hemingway Collection to educate others about Hemingway and his writings on war. The topic of war has also been central to Hemingway forums and conferences organized by the Kennedy Library, including a recent session entitled "Writers on War." And at the Hemingway centennial, held at the library in 1999, many speakers referenced Hemingway's experience in war and his observations on its aftermath as an abiding element of his literary legacy.

Hemingway and World War I

During the First World War, Ernest Hemingway volunteered to serve in Italy as an ambulance driver with the American Red Cross. In June 1918, while running a mobile canteen dispensing chocolate and cigarettes for soldiers, he was wounded by Austrian mortar fire. "Then there was a flash, as when a blast-furnace door is swung open, and a roar that started white and went red," he recalled in a letter home.

Despite his injuries, Hemingway carried a wounded Italian soldier to safety and was injured again by machine-gun fire. For his bravery, he received the Silver Medal of Valor from the Italian government—one of the first Americans so honored.

Commenting on this experience years later in Men at War, Hemingway wrote: "When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality. Other people get killed; not you. . . . Then when you are badly wounded the first time you lose that illusion and you know it can happen to you. After being severely wounded two weeks before my nineteenth birthday I had a bad time until I figured out that nothing could happen to me that had not happened to all men before me. Whatever I had to do men had always done. If they had done it then I could do it too and the best thing was not to worry about it."

Recuperating for six months in a Milan hospital, Hemingway fell in love with Agnes von Kurowsky, an American Red Cross nurse. At war's end, he returned to his home in Oak Park, Illinois, a different man. His experience of travel, combat, and love had broadened his outlook. Yet while his war experience had changed him dramatically, the town he returned to remained very much the same.

Two short stories (written years later) offer insights into his homecoming and his understanding of the dilemmas of the returned war veteran. In "Soldier's Home," Howard Krebs returns home from Europe later than many of his peers. Having missed the victory parades, he is unable to reconnect with those he left behind—especially his mother, who cannot understand how her son has been changed by the war.

"Hemingway's great war work deals with aftermath," stated author Tobias Wolff at the Hemingway centennial celebration. "It deals with what happens to the soul in war and how people deal with that afterward. The problem that Hemingway set for himself in stories like 'Soldier's Home' is the difficulty of telling the truth about what one has been through. He knew about his own difficulty in doing that."

After living for months with his parents, during which time he learned from Agnes that she had fallen in love with another man, he decamped with two friends to his family's Michigan summer cottage, where he had learned to hunt and fish as a young boy. The trip would be the genesis of Big Two-Hearted River—a story that follows one of Hemingway's best known fictional characters, Nick Adams, recently returned from war, on a fishing trip in northern Michigan.

In the story, Hemingway never actually mentions the war and the injuries Nick has sustained in it—they simply loom below the surface. In this and other stories in his first major collection, In Our Time, Hemingway does more than advance a narrative; he also debuts a new style of writing fiction.

"The way we write about war or even think about war was affected fundamentally by Hemingway," stated Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., another speaker at the Hemingway centennial. In the early 1920s, in reaction to their experience of world war, Hemingway and other modernists lost faith in the central institutions of Western civilization. One of those institutions was literature itself. Nineteenth-century novelists were prone to a florid and elaborate style of writing. Hemingway, using a distinctly American vernacular, created a new style of fiction "in which meaning is established through dialogue, through action, and silences—a fiction in which nothing crucial—or at least very little—is stated explicitly."

"Hemingway was at the crest of a wave of modernists," noted fellow centennial panelist and book critic Gail Caldwell, "that were rebelling against the excesses and hypocrisy of Victorian prose. The First World War is the watershed event that changes world literature as well as how Hemingway responded to it."

Return to Postwar Europe

Hemingway returned to Europe after marrying his first wife, Hadley Richardson. His 1923 passport contains a photograph of him as a young, though serious, man. Initially working as a correspondent for the Toronto Star, while living in Paris he grew into a novelist with the encouragement of such Left Bank notables as Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer described Hemingway's motivation to return to Europe as an expatriate this way. After the war, "Hemingway never really came home again." Yet unlike other expatriate writers who were forced to leave their native lands in the face of political persecution, he left the United States of his own volition fueled, in Gordimer's words, by "the beginnings of a broader human consciousness beyond nationalistic operatives, good or bad. And he made his choice of one of the causes in particular—of justice that was threatened in the cultural Mecca of Europe."

As a correspondent, Hemingway chronicled the outbreak of wars from Macedonia to Madrid and the spread of fascism throughout Europe. Although best known for his fiction, his war reporting was also revolutionary. Hemingway was committed above all else to telling the truth in his writing. To do so, he liked being part of the action, and the power of his writing stemmed, in part, from his commitment to witness combat firsthand.

According to Seán Hemingway, his grandfather's war dispatches "were written in a new style of reporting that told the public about every facet of the war, especially, and most important, its effects on the common man, woman, and child." This narrative style brought to life the stories of individual lives in warfare and earned a wide readership. Before the advent of television and cable news, Hemingway brought world conflicts to life for his North American audience.

In 1922, for example, Hemingway covered the war between Greece and Turkey and witnessed the plight of thousands of Greek refugees. In a sight that has become common to our time, Hemingway documented one of the hidden costs of war—the postwar displacement of whole peoples from their native lands. His vivid dispatches brought this and other stories to the attention of the English-speaking world.

Hemingway often used scenes that he had witnessed as well as his own personal experience to inform his fiction. Explaining his technique 20 years later, he wrote, "the writer's standard of fidelity to the truth should be so high that his invention, out of his experience, should produce a truer account than anything factual can be. For facts can be observed badly; but when a good writer is creating something, he has time and scope to make of it an absolute truth."

In Our Time was published in 1925. It was followed by Hemingway's first major novels, The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms, which chronicle, in reverse order, Hemingway's experiences in war and postwar Europe.

The Sun Also Rises features Jake Barnes, an American World War I veteran whose mysterious combat wounds have caused him to be impotent. Unlike Nick Adams and Howard Krebs, who return stateside after the war, Barnes remains in Europe, joining his compatriots in revels through Paris and Spain. Many regard the novel as Hemingway's portrait of a generation that has lost its way, restlessly seeking meaning in a postwar world. The Hemingway Collection contains almost a dozen drafts of the novel, including four different openings—examples of a burgeoning, hardworking, and exceptionally talented young novelist.

His second novel, A Farewell to Arms, is written as a retrospective of the war experience of Frederic Henry, a wounded American soldier, and his doomed love affair with an English nurse, Catherine Barkley.

Hemingway rewrote the conclusion to A Farewell to Arms many times. Among the gems of the Hemingway Collection are the 44 pages of manuscript containing a score of different endings—which are often used today by visiting English teachers to provide their students with a glimpse of Hemingway the writer at work.

At a recent Kennedy Library forum, author Justin Kaplan noted the number of delicate changes Hemingway made to the novel's last paragraphs. When asked once why he did so, Kaplan recounted, Hemingway responded "I was trying to find the right words."

After reading an early draft, F. Scott Fitzgerald suggested Hemingway end the book with one of its most memorable passages: "The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure that it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry." Scrawled at the bottom of Fitzgerald's 10-page letter in Hemingway's hand is his three-word reaction—"Kiss my ass"—leaving no doubt of his dismissal of Fitzgerald's suggestions.

Though World War I is more backdrop than cause to this tragedy—Catherine's death in the end is brought about through childbirth not warfare—the novel contains, as seen in the following passage, a stark critique of war and those who laud it:

I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious, and sacrifice. . . . We had heard them, sometimes standing in the rain almost out of earshot, so that only the shouted words came through, and had read them, on proclamations that were slapped up by billposters over other proclamations, now for a long time, and I had seen nothing sacred, and the things that were glorious had no glory and the sacrifices were like the stockyards at Chicago if nothing was done with the meat except to bury it. There were many words that you could not stand to hear and finally only the names of places had dignity. Certain numbers were the same way and certain dates and these with the names of the places were all you could say and have them mean anything. Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates.

Much of the literature decrying World War I came from British poets, many of whom perished in battle. In A Farewell to Arms, Hemingway added his voice to the chorus, expanding the message to an American audience whose citizenry had not suffered nearly the level of war losses as its European allies. To appreciate the stance that Hemingway took, according to Gail Caldwell, one has to understand how revolutionary it was in light of the Victorian understanding of patriotism and courage. "If you look at Hemingway's prose and the writing he did about war, it was as radical in its time as anything we have seen since."

Commenting on the days and months he spent writing the novel, Hemingway wrote his editor, Max Perkins, that during this time much had occurred in his own life, including the birth of his second son, Patrick, by Caesarian section and the suicide of his father.

"I remember all these things happening and all the places we lived in and the fine times and the bad times we had in that year," Hemingway wrote in a 1948 introduction to A Farewell to Arms. "But much more vividly I remember living in the book and making up what happened in it every day. Making the country and the people and the things that happened I was happier than I had ever been. . . . The fact that the book was a tragic one did not make me unhappy since I believed that life is tragedy and knew it could only have one end. But finding you were able to make something up; to create truly enough so that it made you happy to read it; and to do this every day you worked was something that gave a greater pleasure than any I had ever known. Beside it nothing else mattered."

The Spanish Civil War

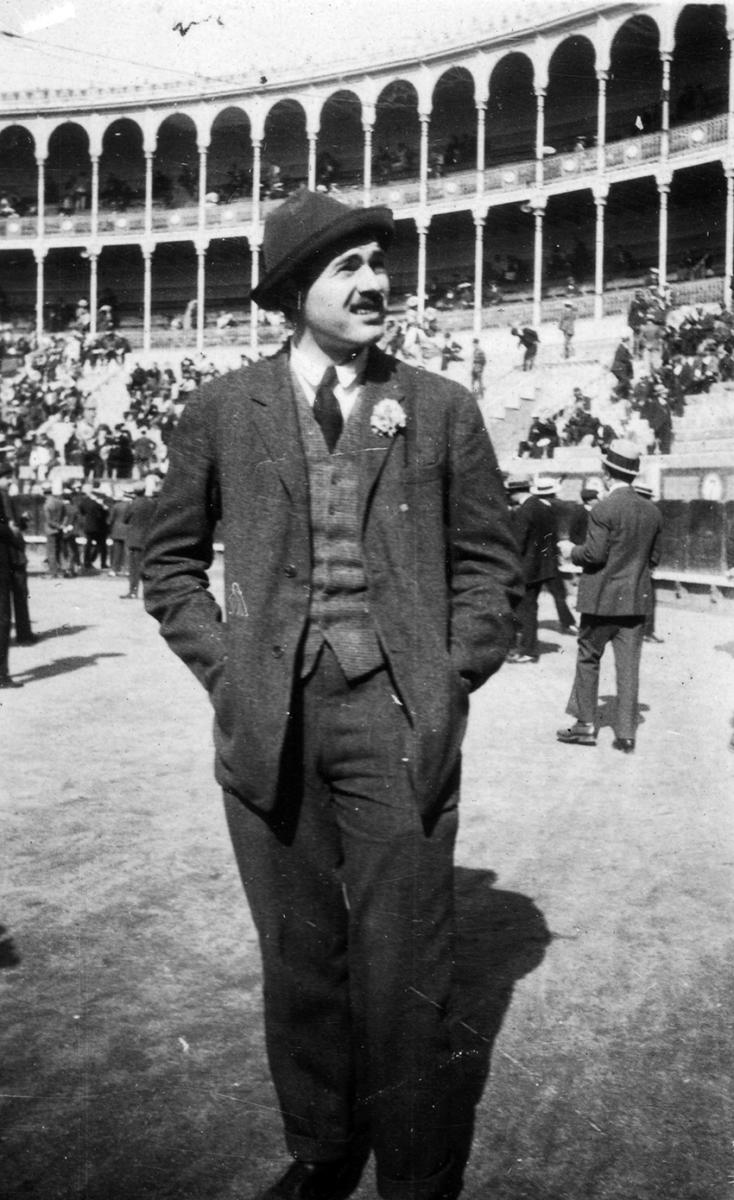

Hemingway had an enduring love affair with Spain and the Spanish people. He had seen his first bullfight in the early 1920s, and his experience of the festivals in Pamplona informed his writing of The Sun Also Rises. The Hemingway Collection contains the author's personal collection of bullfighting material, including ticket stubs, programs, and his research material for his 1931 treatise on bullfighting, Death in the Afternoon. So it is not surprising that as fascism spread throughout Europe, Hemingway took special interest when civil war broke out in Spain.

Hemingway first encountered fascism in the 1920s when he interviewed Benito Mussolini, a man he described as "the biggest bluff in Europe." Although others initially credited Mussolini for bringing order to Italy, Hemingway had seen him for the brutal dictator he was to become. In fact, Hemingway dated his own antifascism to 1924 and the murder of Giacoma Matteotti, an Italian Socialist who was killed by Mussolini's Fasciti after speaking out against him.

In Spain, Francisco Franco, with support from Germany and Italy, used his Nationalist forces to spearhead a revolt against the government and those loyal to the Republic. When civil war broke out, Hemingway returned to Spain as a correspondent for the North American Newspaper Alliance, serving, at times, with fellow journalist Martha Gellhorn, who would become his third wife.

While in Spain, Hemingway collaborated with famed war photographer Robert Capa. Capa's photographs of Hemingway during this period are now part of the Hemingway Collection's extensive audiovisual archives of more than 10,000 photographs.

Hemingway's coverage of the war has been criticized for being slanted against Franco and the Nationalists. In a 1951 letter to Carlos Baker, Hemingway explained it this way. "There were at least five parties in the Spanish Civil War on the Republic side. I tried to understand and evaluate all five (very difficult) and belonged to none. . . . I had no party but a deep interest in and love for the Republic. . . . In Spain I had, and have, many friends on the other side. I tried to write truly about them, too. Politically, I was always on the side of the Republic from the day it was declared and for a long time before."

"It is the duty of a war correspondent to present both sides in his writing," contends Seán Hemingway, and in this instance, Hemingway "failed to do so siding as he did so strongly with the Republic against the Nationalists." Yet his dispatches provide a vivid accuracy of how the war was fought—and his experience would later inform his writing of For Whom the Bell Tolls. Despite his sympathies for the Loyalist cause, he is credited for documenting in this novel the horrors that occurred on both sides of that struggle.

The novel's protagonist, Robert Jordan, an American teacher turned demolitions expert, joins an anti-fascist Spanish guerrilla brigade with orders from a resident Russian general to blow up a bridge.

For author Gordimer, what is remarkable about the novel (which she describes as a cult book for her generation) is that Jordan takes up arms in another country's civil war for personal, not ideological, reasons. In the novel, Hemingway suggests that Jordan has no politics. Instead, his dedication to the Republic is fueled, in Gordimer's words, by a "kind of conservative individualism that collides in self-satisfaction with the claims of the wider concern for humanity." Jordan dedicates himself to a cause and is willing to risk his own life for it.

The bridge gets destroyed, his compatriots flee, and Jordan is left behind, injured, to face certain death at the hands of the approaching fascist troops. It is perhaps because of his commitment to action that Jordan became such a cult figure for his times. In his own words from the novel: "Today is only one day in all the days that will ever be. But what will happen in all the other days that ever come can depend on what you do today. It's been that way all this year. It's been that way so many times. All of war is that way."

World War II and Its Aftermath

In 1942 Hemingway agreed to edit Men at War, an anthology of the best war stories of all time. With the United States now at war, Hemingway remarked in the introduction: "The Germans are not successful because they are supermen. They are simply practical professionals in war who have abandoned all the old theories . . . and who have developed the best practical use of weapons and tactics. . . . It is at that point that we can take over if no dead hand of last-war thinking lies on the high command."

Not one to sit about or practice the "dead hand of last-war thinking," Hemingway, living in Cuba when the war broke out, took it upon himself to patrol the Caribbean for German U-boats. The Hemingway Collection contains many entries in the day log of his boat Pilar and his typewritten reports to local military commanders indicating how carefully he recorded his sightings and passed them on to American intelligence officials.

In 1944 he returned to Europe to witness key moments in World War II, including the D-day landings. He was 44 at the time and, comparing his photograph on his Certificate of Identity of Noncombatant to the portrait of the young 19-year-old who volunteered in World War I, one notices how distinguished the internationally renowned author had become in those 25 years.

Hemingway accompanied American troops as they stormed to shore on Omaha Beach—though as a civilian correspondent he was not allowed to land himself. Weeks later he returned to Normandy, attaching himself to the 22nd Regiment commanded by Col. Charles "Buck" Lanham as it drove toward Paris (whose liberation he would later witness and write about). Before doing so, Hemingway led a controversial effort to gather military intelligence in the village of Rambouillet and, with military authorization, took up arms himself with his small band of irregulars.

According to World War II historian Paul Fussell, "Hemingway got into considerable trouble playing infantry captain to a group of Resistance people that he gathered because a correspondent is not supposed to lead troops, even if he does it well."

On June 23, 1951, Hemingway wrote to C. L. Sulzberger of the New York Times with his own explanation: "Certain allegations of fighting and commanding irregular troops were made but I was cleared of these by the Inspector General of the Third Army. . . . For your information, I had an assignment to write only one article a month for Colliers and I wished to make myself useful between those monthly pieces. I had a certain amount of knowledge about guerilla warfare and irregular tactics as well as a grounding in more formal war and I was willing and happy to work for or be of use to anybody who would give me anything to do within my capabilities."